Struggling with the Youth Guarantee

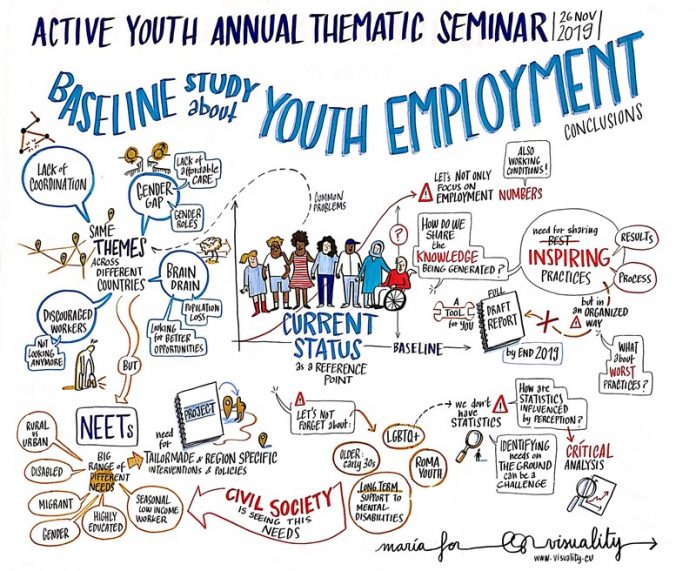

Since its adoption in 2013, the European Youth Guarantee (YG) and the Youth Employment Initiative and European Social Fund resources it has mobilized (€9 billion over the 2014-2020 period) has clearly become the central tool to cope with youth unemployment challenges all throughout Europe. The contributions to the Baseline Study on Youth Employment in the 15+3 beneficiary countries of the Youth Employment Fund (YEF) that we are preparing make it clear. To this extent, the way the YG is working is of crucial importance for European societies, for their present and their future. Discussions held in the thematic seminar held in Brussels on the 25-26 November revealed that civil society organizations active in the field of youth employment have a deep knowledge of the Youth Guarantee and highlighted some dysfunctions in what is largely considered as a very good idea: nothing less that “a commitment by all Member States to ensure that all young people under the age of 25 years receive a good quality offer of employment, continued education, apprenticeship or traineeship within a period of four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education”.

The European Commission [1] duly reports on problems of implementation in the different countries such as the tracking and counting system of potential beneficiaries, capacity of public employment services, the degree of coverage (share of registered potential beneficiaries taken in charge by the Youth Guarantee), the effectiveness (share of beneficiaries who get an employment or training offer within four months) and short-term impact (percentage of beneficiaries which are in a positive situation after six months of leaving the scheme), as well as issues of coordination among institutions and fragmentation of actions. They are even ready to admit the insufficiency of allocated budgetary resources (and have increased significantly budget appropriations over the period of implementation of the YG).

But discussions in the YEF thematic seminar in Brussels echoed the need for a more structural discussion and a more articulate involvement of civil society in the implementation of the Youth Guarantee. These are some of the points raised by participants:

- Uniformity. As clearly emerging from the national contributions to the Baseline Study, the YEG is being implemented in very much the same way throughout all the European countries. To this extent, it lacks the sensitiveness and flexibility needed to respond to the specific challenges encountered in different countries and regions or in relation to different target groups.

- Scope. The Youth Guarantee basically targets registered unemployed young people. However, the main groups of youth neither in employment nor in education are either inactive (in particular young women) or discouraged (as it is often the case for youth minorities, in particular if difficult youth employment situation combines with social discrimination, as it is the case for Roma or young immigrants), and they are not reached by YG actions.

- Short-term actions, long-term vulnerabilities.The YG is conceived as a “rapid intervention” programme. This is of course appreciated, but has some unintended consequences: for groups of youth unemployed which need a long-term commitment, for instance young persons with disabilities, the short-term actions provided for in the YG do not offer a real path for stable employment over time. The same happens, actually, for many of the beneficiaries of the YG overall: they tend to chain training courses with short lapses of employment (often even informal), subsidized work for some weeks or months, unemployment periods again, other trainings….This contributes to improve youth employment statistics, but not necessarily long-term employment and life prospects of the beneficiaries.

- Crowding out. YG actions are basically implemented through State and local authorities institutions. Even if they often capitalize on pilots and experiences from civil society organizations, the massive resources mobilized translates into a kind of unfair competition for the latter, who sometimes have even difficulties to compete with the incentives offered by the YG and to find beneficiaries of their programmes.

The thematic seminar in Brussels and the discussion of the Baseline Study revealed two things:

- Six years into implementation, a thorough public debate is due, at European and at national level, to assess how the Youth Guarantee is working and how it could be improved for the new 2021-2027 to better tackle the specific needs and challenges of youth employment and remedy its shortcomings and dysfunctions in each local context in Europe.

- Civil society organizations, practitioners of youth employment promotion at local level, have to be more systematically associated to this debate, but also to the implementation of the Youth Guarantee. The 200+ partners in the Youth Employment Fund projects have a hands-on, on-the-ground knowledge and expertise that cannot be ignored when we deal with the main youth employment promotion policy tool we have today in Europe.

Iván MARTÍN

Our Spanish Youth Employment Expert

[1] See The Youth Guarantee country by country,https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1161&langId=en.