The main goal of the paper is to introduce into the pro-innovative aspects of several chosen systems of education in Europe which have succeeded in last decade in effective results of primary and post-primary schools. Therefore we have done a short review of Dannish, Finnish, Irish and German systems of education from the perspective of social and pedagogical innovations.

Let us start from key report on pro-innovative skills in some Polish schools and in the comparative context for us which also have been collecting variety international experience combined in the publish called „Szkoła dla innowatora. (2018). Kształtowanie kompetencji proinnowacyjnych”. Basing on the report, we may shortly present a systematization of definition of ‘innovation’ meaning in the area of education and social science:

The word “innovation” comes from Latin and means renewal or renovation (Williams 1999; Clapham, 2003). The concept is different from the concept of creativity by that, in the case of innovation, we can talk about implementing a solution without creativity in a new context. However, the definitions of innovation and creativity will differ due to the application nature of innovation. Williams (1999) and Clapham (2003) believe that innovation occurs when people create new solutions that are accepted by members of the community as useful and adequate to the current needs of the community. Innovation requires knowledge (OECD, 1997) and is considered to be the implementation and application of new knowledge (Jaumotte and Pain, 2005). According to the definition of the European Commission (2001, 2003), innovation is understood as activities that lead to the launch of a new product or a new production method (Szkoła dla innowatora…, p. 14, 2018).

Both ‘innovation’ and ‘creativity’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ are concepts – at least in certain areas – identical or synonymous. For example, an entrepreneur often has to use his creativity. An innovator may or may not become an entrepreneur; creative people often become innovators, and when they commercialize their ideas, they become entrepreneurs (Szkoła dla innowatora…, p. 15, 2018).

To sum up, creativity is the ability to create ideas and concept (Amabile, 1983) or new ways of solving problems. Innovation is the ability to implement creative solutions to solve these problems or use new opportunities (Kabakcu, 2015). The concepts of creativity, entrepreneurship and innovation are closely related to each other. Especially if we consider that creativity takes the domain-specific form, i.e. most people (with few exceptions, e.g. Leonardo da Vinci) are creative in certain areas. Shaping pro-innovative competences serves the development of society and should not be limited only to economic activity (Szkoła dla innowatora…, p. 16, 2018).

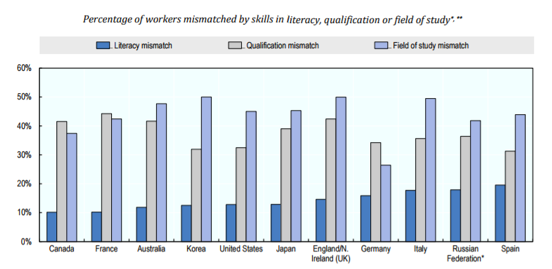

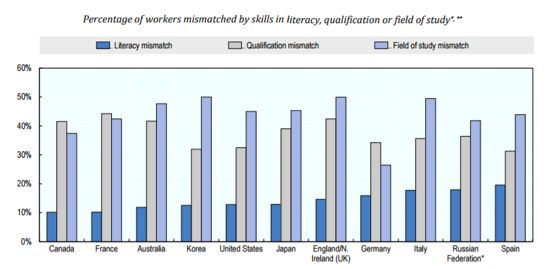

There is no question that education improves a young person’s chances of securing a better quality job, and increases student’s productivity and income. Although a broadly positive view towards students’ education, significant numbers of young people across all markets question how well their academic experiences equipped them for their career. Half of young people in Germany, Australia and the US believe that their education did not prepare them for what to expect from working life (Infosys, 2016). What is worse, over 40 percent of Europeans employed in the labour market of Europe claim that their skills and qualifications are higher than the lower skill jobs they applied or they do.

Looking over Atlantic, in the United States there can be observed the mismatch between the skills possessed by much of the U.S. workforce and the skills required by U.S. employers. Both students’ expectations for what they must learn and schools’ expectations for what they must teach have not adapted quickly enough to changes in the economy. The skills gap described above indicates, however, that education systems have not changed globally at the same pace as the economy. It seems to be another gap if we take into account the factor of difference between countries’ economy. There is the gap between emerging and developed nations in terms of their readiness for the future of work. Moreover, should such trends continue, this division between the ‘high-tech haves’ and ‘high-tech have-nots’ will widen across all markets. For instance, young people in emerging markets are most confident that they have the skills necessary for a successful career. Across Brazil, India, China and South Africa, respondents show much greater confidence in their skill-set than their peers in developed markets. For example, while 60% in India agree they have the skills needed for a positive career, just 25% agree in France (Infosys, 2016). In many industries and countries, the most in-demand occupations or specialties did not exist 10 or even five years ago, and the pace of change is set to accelerate. By one popular estimate, 65% of children entering primary school (World Economic Forum, 2016).

In 2011, a survey of 2,000 U.S. companies revealed that two thirds of these companies reported difficulties finding people qualified to fill some of their open positions (Manyika, Lund, Auguste, Mendonca, Welsh & Ramaswamy, 2011). Furthermore, some positions had remained open for at least 6 months in 30% of these companies. In addition, a 2006 survey of 431 employers across the United States found that, in terms of their perceived level of readiness for entry-level jobs, 40% rated high school graduates as deficient, 30% rated 2-year college graduates as deficient, and 36% rated 4-year college graduates as deficient (Casner-Lotto & Barrington, 2006).

We have to remember that a skilled workforce goes hand in hand with economic growth. Skills development needs to be part of a comprehensive, integrated strategy for growth that improves the lives of all. The question is not whether creating jobs or developing skills comes first; both need to be pursued in a coherent, integrated manner. Investing in skills training and education is smart; for every US dollar invested in skills and education in developing countries, US$10-15 is raised in economic growth (Hanushek & Woessmann, 2011).

The core work skills which enable individuals to constantly acquire and apply new knowledge and skills, they are also critical to lifelong learning. Core employability skills build upon and strengthen those developed through basic education, such as reading and writing, the technical skills needed to perform specific duties, such as nursing, accounting, using technology or driving a forklift and professional/personal attributes such as honestly, reliability, punctuality, attendance and loyalty (Brewer, 2013). These skills have been labelled differently by various agencies and organizations (Table 1). Not only are these variably labelled, the incumbent skills differ, depending on the definition and scope adopted as well as the level/type of employment under discussion. There is also a developed country bias in the literature covering this area of skills development, for example if we look at the variety of depicting terms.

| Country | Terminology |

| United Kingdom | Core skills, key skills, common skills |

| New Zealand | Essential skills |

| Australia | Key competencies/employability skills/generic skills |

| United States | Basic skills, necessary skills, workplace know-how |

| Singapore | Critical enabling skills |

| France | Transferable skills |

| Germany | Key qualifications |

| Switzerland | Trans-disciplinary goals |

| Denmark | Process independent qualifications |

| ASEAN | Employability skills |

| Latin America: | Key competencies, work competencies |

| European Commission | Key competencies |

| OECD | Key competencies |

| ILO | Core work skills/core skills for employability |

| EFA-GMR | Transferable skills |

Table 1. How skills and competences have been labelled in different countries (source: Brewer, 2013, 7).

This table above also points out the issue of different approach towards certain skills becomes evident and certain skills recur throughout. Clearly some skills are more relevant than others depending on the type of employment, culture, the sector, the size and nature of the enterprise, whether self-employed or working in the formal or the informal economy. We should take into account cultural and anthropological factors and conditions which affect such choices of proposed skills. All this in addition takes place in so changeable environment. Therefore, substantial changes in skill needs are likely to generate skill shortages and mismatch (Table 2). In most countries, training systems lag behind changes in demand for skills. In others, upward trends in average educational attainment are unmet by demand in the short run. For some young people, this may be part of the process of “job-shopping” to find the best job that suits their skills.

Essentially, training systems, governments, individuals and employers will have to become more adaptable and responsive to changing skill needs. For employers, this means: working with education institutions to ensure the provision of relevant skills and the availability of apprenticeship places; providing on-the-job training to prevent skills aging; and adopting forms of work organization that make the most of existing skills. For employees and job seekers, adaptability translates into better employability through the acquisition of skills that are relevant to labor market needs and transferable to different sectors and technologies. The flexibility of education and training systems need to be enhanced to respond more promptly to emerging skill needs. The adaptability of the workforce should be encouraged through the development of transferable skills, broader vocational profiles and competency-based training delivered through work-based learning, including quality apprenticeships (Enhancing employability, 2016). Finally, governments can promote adaptability through the provision of quality career-guidance systems, by ensuring that labor market institutions and policies boost demand and encourage job creation and addressing market and government failures that keep employers from being able to adapt on their own (e.g. access to credit to fund in-house training programs, or certification standards for certain skill categories) (Enhancing employability, 2016).

So this enhancement of records especially after crisis od 2008 points the global economic optimism. As some new diagnosis show young people today become more optimistic generation in the face of a challenging future. Across global markets two-thirds feel positive about their job prospects while a similar number recognize that global forces will continue to increase competition and complexity in the labor market (Infosys, 2016) [1].

[1] The research was conducted via a 20 minute online survey among 1,000 16- to 25-year-olds in each market surveyed (except for South Africa where the sample was 700). Quotas were applied to ensure a near 50/50 split between gender and between the 16-18 and 19-25 age bands in each market. Markets were surveyed in Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, South Africa, UK and US.

Identification of post-innovation competences

Already in 2015 in the United States, 21% of all jobs were related to the use of creativity by employees. The World Bank research shows that the so-called soft-skills are the most unique skill set sought by employers. For example, teaching preschoolers perseverance and cooperation skills is more justified than preparing them into the ability of creating business plans papers.

Basing on the EU project “Transformers”, which we were running with our Scandinavian partners (from Finland, Sweden, and Italy) we have analyzed several dozen studies, including OECD reports on pro-innovation competences, creativity and related issues (including OECD 2007). We managed to isolate from the mentioned report (Szkoła dla innowatora…, p. 20, 2018) the “long list” of over 150 competences defined by the authors also as values, features, attitudes. These include:

- Generating ideas;

- Critical thinking;

- Knowledge synthesis / reorganization;

- Creative problem solving;

- Problem identification;

- Search for improvements;

- Collecting information;

- Independent thinking;

- Knowledge of technology;

- Openness to ideas;

- Cognitive curiosity – willingness to empirically verify one’s assumptions;

- Ability to cooperate;

- Engaging in non-work related interests;

- Ability to identify problems and challenges;

- Assessment and analysis of long-term consequences of phenomena and activities;

- Visionary;

- Empathy;

- Challenging the status quo;

- Intelligent taking calculated risk;

- Striving for improvement;

- Openness to changes;

- Increased risk acceptance;

- Tolerance for ambiguity (Szkoła dla innowatora…, p. 20, 2018).

In many countries of the world, programming is already beginning at primary and even pre-school level. It is also worth noting that pro-innovation skills are not only taught in formal education. For example, toy manufacturers produce robots to learn programming at home (Szkoła dla innowatora…, p. 21, 2018).

Curiosity is a natural feature of young person, and the school can strengthen or develop it, or supress it, e.g. in science classes, cognitive curiosity is best developed by engaging students in such a way that teachers create the chance to ask questions, search for information, and allow students to draw conclusions independently (McCrory, 2010). So for the development of pro-innovation competences, it is necessary to provide deep learning. We live in a time when the nineteenth-century school model became completely outdated. Changes in the socio-economic environment and new challenges require us to take action to change the model of the school’s functioning. Changing the school model requires defining pro-innovative competences, and then building a teacher education system and organizing school work.

We chose four examples of innovative systems of education in Europe to review shortly in order to compare the good practices and effective solutions. Let us start from Danmark.

The Danish education

The Danish education system promotes interdisciplinary learning – each subject should be taught using various teaching aids and include elements of developing literacy, movement, creativity and innovation as well as the ability to work with modern technologies. Regardless of the issue, the student should be able to (Szkoła dla..,p. 37, 2018):

- Assess the problem and its potential value and impact on the environment of other users (entrepreneurship and innovation);

- Find and critically evaluate information on a given topic using online resources;

- Understand and write a professional text (appropriate for your level) using appropriate specialized vocabulary.

Work in a Danish school is focused on project work. The implementation of projects using the “FIRE – Faser – Design Process Thinking” methodology is new. The method taken from the field of designing functional objects is based on 4 stages, according to which students work divided into design groups. The process consists of the following phases:

- Understanding (based on empathy).

- Defining the problem – when defining the problem, the questions “who is the solution to be used for?”, “Why?”, “What should be the final effect” be used?

- Generating ideas – students focus on generating as many possible solutions as possible for the defined problem. Students learn to respect the ideas of others and not judge them prematurely.

- Implementation and testing – students try to build the first prototype that serves as the basis for further reflection and deepening the issue (Szkoła dla..,p. 37-38, 2018).

The following pro-innovation competence development programs are implemented in Danish education:

- “Skills for the Future” – the project involves additional classes for students and a competition for vocational secondary schools for classes with a car profile. Participation in the project provides a guest school conducting classes by the Hyundai group in Denmark.

2. “Company program” – consists of learning by doing and is intended for students of all types of high schools; - “Next Level” – is an educational program run by the Danish Enterprise Foundation and is aimed at grades 8-10 of primary schools. The goal of the program is to provide opportunities to develop skills through entrepreneurship activities.

4. “Edison” – a project directed to pupils in grades 6-7 of primary school, based on inventiveness (Szkoła dla..,p. 39, 2018).

During classes, especially in the area of natural sciences, teachers use a variety of support materials that help students understand abstract concepts (Szkoła dla.., p. 40, 2018):

1. Using the offer of local museums and science centers.

2. Preparation of the presentation.

3. Visualization of concepts through movement – the school must provide students with a minimum of 45 minutes of movement per day. Movement is understood as part of a broader field, which is physiology, health and science of nature.

Group work is a standard at work in a Danish school. The class is divided into smaller teams that simultaneously work on the selected issue. When finished, they present their projects to other groups. In Danish schools, the implementation of projects with the participation of external institutions is promoted – students participate in initiatives with the participation of local experts (e.g. carpentry workshops, sports clubs), visit senior clubs, where they present their knowledge and projects. Responsibility for progress – self-assessment – is one of the elements of the school reform to encourage students to self-assessment their own learning progress. Denmark’s results in international tests show improvement. There is a flexible timetable in Danish schools – this applies to all primary school classes. The solution used in Virum since 2000 consists in changing the plan every 3 weeks (Szkoła dla.., p. 41, 2018).

The Ministry of National Education of Denmark in the “guidelines for teaching innovation and entrepreneurship” defines four areas and educational goals that are evaluated at the final evaluation of pro-innovation competences: action, creativity, knowledge of the world, personal attitude (Entrepreneurship Education, 2014). Increased role of school educators – to achieve the ambitious goals of the reform, close cooperation between teachers, educators and other school staff is necessary. In grades 1-3, the teacher can act as a teacher.

An example from Finland

One of the successful approaches in education but also in preparing individuals into competing and gaining new competences and skills are implemented educational solutions and innovations in Finland; it has been stillthe successful system of introducing social and education innovations in Europe and on the globe. Even if we compare two approaches of so far liberal but public as well approaches we are able to notice important differences in forming future intellectual and personal potential. For almost two last decades we have also admired the consistency and the success of Finland’s educational paradigm. Among the achieved results, emerges the conclusive understanding that there are successful alternative educational systems that are deeply opposed to the global corporate standard of education, and which can serve as educational models for other nations (Bastos, 2017).

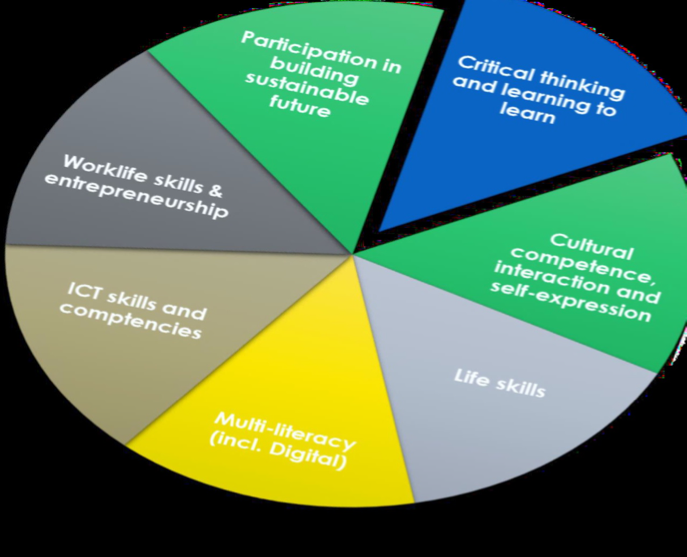

Figure 11 shows the Finnish Educational Designion as presented by Tiina Malste in the Finnish Embassy in Warsaw; Discussion Event on Finnish Education, Warsaw, Poland on May 8, 2019.

What is remarking in this comparison on the side of Finnish paradigm there is an focus on the individual learner/student who is in the center and is the core of all educational and skilling activities and paid attention all around. Therefore as we can observe at the above table such skills as creativity, risk taking, own responsibility, own sort of scaled experience, individualization…etc. are so significantly important for Finnish educators, teachers or counselors… in dealing with their listeners/pupils/students…etc. and serving them all the time regardless of their family background, socioeconomic status or any other factors or conditions. We should add that such values of relationships as trust and belief laid down as core stone of consistently built fine system of education.

Such Finnish Way of preparing future intellectual capacity and workforce potential generates high ranking achievements and positions for example in the remarkable research of achieving skills – PISA. Finland’s remarkable performance in the tests carried out in last decade by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (henceforth OECD) in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is quite striking.

The dissemination of these results has shaken the world’s academic and political status quo. Finland, a distant country located at the northern end of the globe, surprisingly, takes the first places in the three cognitive domains evaluated by the test, namely Mathematics, Science and Reading, the latter as a priority focus of that round of PISA (whereas, in the 2003 round, priority was given to Mathematics and, in 2006, to Science). What is more these outstanding results have been generally maintained: Finnish students’ performance in the following examination rounds (2003, 2006, 2009 e 2012) repeats the excellence standard recorded in the first round of first decade of 21st century, which consolidates the perception of the consistency and the soundness of the northern European country’s educational system, awakening the curiosity and the worldwide avalanche of analyses and researches on the fundamentals and the reasons of the success of its educational model.

Among the achieved results, emerges the conclusive understanding that there are successful alternative educational systems that are deeply opposed to the global corporate standard of education, and which can serve as educational models for other nations (Bastos, 2017).

In the education promoting tendency that instead of teaching process the stress has been put on learning: particularly focusing on objectives and competencies rather than content; also focusing on the joy of learning, collaborative operational culture, promoting student autonomy and accountability, individualizing learning paths…etc. The Finnish approaches so successful in effects of holistic learning especially stressing the idea „no student left behind” are proposing also some crucial structure of applied skills and competences which is worth to consider as well (Figure 1)

The example of Finnish education is still the most successful system implemented into practice and what PISA index report proves almost every year it is the most effective too.

Finnish teachers enjoy great freedom in the selection of methods and teaching aids. The great social trust that the profession has in Finland means that the teacher’s working methods are not questioned or even carried out any detailed teaching control. A flexible approach to the teacher’s work method is also transferred to student evaluation methods. Finnish students pass only one state examination at the end of primary school, and the annual and semester marks for the first few years are only descriptive.

The national primary curriculum contains the goals and basic elements of teaching each subject. Includes both student assessment rules, specialty education, student well-being, and education guidelines.

In accordance with the reform assumptions, the basic objectives of the new core curriculum are:

1. Developing schools as educational communities;

2. Shaping the joy of learning and the student’s natural curiosity;

3. Taking care of the atmosphere of cooperation;

4. Promoting student autonomy in learning and school life (Szkoła dla..,p.44, 2018)..

To meet the challenges of the future, schools are to focus on developing interdisciplinary competences. These are:

- Learning to learn;

- Communication competences: interaction, expressiveness;

- ICT competences;

- Multi-literacy and the ability to explain complex texts;

- Innovation and entrepreneurship;

- Ability to organize own work (Szkoła dla..,p.45, 2018).

Local Finnish authorities and schools are encouraged to develop their own innovative ways to achieve goals. The new program also introduced interdisciplinary teaching and experience-based projects. According to such laid down goals the Finnish pupils and students should participate in the project planning process. Teachers freely choose working methods taking into account the goals set in the curriculum. The Finnish core curriculum includes general guidelines and recommendations on teaching methods and materials without specifying details (Szkoła dla..,p.45, 2018).

Finnish teachers enjoy great trust and social respect – they independently choose working methods suitable for different age groups and educational situations, and his choices are not questioned. The techniques used that support the development of pro-innovative competences and stimulate the student’s natural curiosity include:

- Experimental and functional working methods, the involvement of different senses and the use of movement increase the empirical nature of learning and strengthen motivation.

- An experimental and problem-oriented approach to work, role playing, the use of imagination and artistic activities promotes conceptual and methodical competence, critical and creative thinking.

- Working methods supporting the student’s development as a member of the group, where competences and skills are acquired through interaction with others (Szkoła dla..,p.46, 2018)..

When working with a student, the opportunities offered by games and activities are used. Students enjoy a great deal of freedom both during class and in the school space. Children move around the school building on their own, usually they also go to it and come back, using public transport. The Finnish school emphasizes the importance of learning through experience and puts special emphasis on group work, creativity and problem solving.

Teachers conduct lessons according to their own concept to fit into their class and devote adequate attention to students. Less hours of standard learning with a teacher mean more time for individual work and for developing independent and critical thinking. The abolition of the division into primary and vocational school leveled the educational opportunities and eliminated the divisions due to intellectual predispositions.

Students are brought up so as to respect the opinions of others and are not afraid to choose their own paths of reasoning. Although officially no tests or detailed assessment of the student are carried out at the Finnish school during the school year, Finnish teachers use a wide range of diagnostic tests and screening tests to make sure that none of the students leave – especially in reading (Szkoła dla..,p.47, 2018).

One of the interesting pro-innovative and educational programs is the LUMA. The LUMA FINLAND program implemented by LUMA Center Finland aims to inspire and engage children between 6-16 years in the field of science, technology and mathematics (Strategy…, 2019). The student is assessed on the basis of observation of his progress and behavior during classes (especially group work). Finnish teachers use the method of grading students by walking around the classroom and watching the progress of each group. The lack of a strict numerical assessment system and the necessity to carry out tests in primary education mean that students do not feel the need to “demonstrate” for the purposes of short-term effects or rewards in the form of assessment (Strategy…, 2019).

On the other side of Europe we can make comparison to the Irish system of education in approach to pro-innovative competences. In the Irish education system, both in primary and secondary school, a very strong emphasis is placed on developing literacy and numeracy skills, these skills being understood broadly: reading skills include reading comprehension, a critical approach to content transmitted through various forms of communication (spoken language, printed text, traditional media, electronic media).

Counting skills are not narrowed to performing arithmetic calculations, they take into account the whole group of competences related to the use of mathematical reasoning to solve problems, including everyday problems in a complex economic and social environment. The Maths project has been in operation since 2008 – there is a team of mathematicians under the project who advise mathematics teachers on developing students’ mathematical competence (Szkoła dla.., 2018): .

The primary school curriculum is intended to provide children with a wide spectrum of experiences and encourage them to learn, and to serve the child’s holistic development: spiritual, social, physical, moral, cognitive, emotional, develop imagination, and develop aesthetic senses. Primary education consists of two cycles: junior cycle and senior cycle (Szkoła dla.., 2018):.

As part of the junior cycle, six key competences to be developed in schools were distinguished:

- managing myself;

- staying well-being healthy both physically and mentally and having the competence to take care of themselves and caring for others is to enable students to feel happy and be confident;

- cooperation with others;

- communication (communicating);

- creativity – this element of the curriculum is to develop imagination and creativity;

- information management and reasoning – these skills are designed to gradually help students search for information from various sources;

Each of the key competences planned for the junior and senior cycle is detailed by a bunch of learning outcomes. Descriptions of learning outcomes are formulated in such a way as to indicate to teachers and students what competences are to be developed and verified during school education.

It is also worth adding that for each key competency described in the Irish curricula, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment has developed textbooks for teachers to help them develop these competences as part of school activities.

The six main teaching methods are used in Irish curricula:

- conversation and discussion;

- active learning – classroom discussions, visualization-based instructions, essays, debates, staging organizations, simulations and role modeling;

- collaborative learning;

- problem solving (problem solving);

On the conclusion of our short review we propose to look at a German case of dealing with pro-innovative skills and competences.

One of the pro-innovative competences developed in the German education system is the development of student curiosity and learning about various possibilities. An example of learning history can be classes on the French Revolution, in which students propose common questions on this topic (e.g. in the form of a mind map) to determine what information is known to them, and what turns out to be logically inconsistent or doubtful (Szkoła dla.., 2018).

In addition, teachers often use problematization of the topic of classes by provoking students by means of contrasts, contradictions, comparisons or exaggerated formulations, and thus encourage them to critically referring to the topic of classes and develop self-awareness. The Morsum elementary school in Sylt-Ost uses open learning methods that support students’ cognitive abilities, e.g. free work, time to read, time for exercises, design phases or days for practical classes in a workshop or printing house (Szkoła dla.., 2018).

The method that allows you to develop interest in a new topic is to learn from other students who prepare the topic and transfer knowledge to their classmates. Methods supporting independent thinking include chain of stories in which the teacher’s broadly asked question is answered in turn one by one, adding new threads to the statements of the previous speakers as long as certain rules of the game are not broken.

In the method of making statement, students receive text on current socio-political topics, historical events or problems of philosophy. Another example of teaching and assessment methods that develop independent thinking is project work, in which participants must independently develop analytical tools, e.g. design a questionnaire, which is then passed on to other students or school staff.

The ability to think independently is developed in German schools, including by the method of a double circle (internal and external) of chairs with an equal number of seats, with the students of both circles sitting opposite each other and discussing, e.g. the content of the text they read or the film watched (3 min.) (Szkoła dla.., 2018).

In older classes (e.g., 9-10), role-playing related interviews are often used as part of economic classes to help students understand the perspective of the employer and the potential employee. In Germany there are youth games in which students from the youngest classes can participate without pressure on the results, with the aim of developing passion. In order to identify predispositions and interests, students can participate in several competitions.

In order to identify predispositions and interests, students can participate in several competitions. An important aspect of the sustainable development of students is the development of interests, because the motivation to act results from them, and thus the competences discussed in this analysis are supported.

In the federal state Rhineland-Wesfalia, there is the Medienpass initiative, which develops teaching materials for all classes to develop awareness of the conditions, objectives and effects of media functioning. At the federal state level, there are forms of student government representing the interests of students from all territorial units. Student ombudsmen of individual municipalities support their candidates for student councils at the Ministry of Education (Szkoła dla.., 2018).

Bavarian ‘Echt Kuh-l!’ Projects is informed and passed to students in classes 3-10 with the problems and challenges of the green economy, e.g. students from one of the program editions analyze the origin of various regional products. The project combining practical skills with a focus on sustainable development is the project “Green Hack – Open Innovation for Climate”, consisting in the development of a mobile application related to environmental protection (Szkoła dla.., 2018):.

The technical capacity of students is shaped at the design stage of the curricula at the level of the German federal states. The Informatik – AG work community led by Data Experts offers students in classes 8-12 training in programming and other IT skills. A similar role is played by international scientific competences called “olympiads” (in the field of individual disciplines or multidisciplinary), competitions in the field of mathematical and natural research (‘Youth studies’), annual IT competitions at the Federation level, as well as the inter-school competition ‘Tech Discoveries’.

Conclusion

The most interesting from the Polish point of view and quite easy to accept are the Danish experiences in education. There are used the quite uncomplicated and interesting educational solutions; although simple, in Poland they would still encounter mentality barriers on the part of students and their parents either, as well as competence barriers when it comes to implementation issues.

Danish solutions require openness and enthusiasm from the teacher in combination with organizational skills and self-discipline at work. Hence, from the educational and organizational solutions of Scandinavian, American or Israeli one can derive a pragmatic approach, also manifesting itself in the strong creation of a school and a place where students learn primarily how to solve problems. Which at the same time shows how to attract not only the educational process, but above all the institution of the school. On the other hand, looking at German experience, it can be stated that teaching pro-innovative competences does not have to follow a universal agenda; that it can be developed own solutions taking into account internal systemic and cultural conditions.

It is also worth noting that in countries such as Finland, South Korea and Israel, great attention is paid to equalizing educational opportunities for students. In these countries, there are the best teachers who are just directed to the most difficult places and environments, unfortunately, in the case of Polish system of education – we have the impression – that the opposite is still happening. It is better with the process of personalizing knowledge in teaching in Poland, however, the idea of “no left student behind” requires greater implementation and popularization at all levels of teaching.

There is no doubt that the synthesis of good practices should be done very carefully and take into account the educational specifics of a given country, but certainly in Poland and in most countries learning pro-innovative skills and competences should be put towards the long-term goal in order to that today’s students can relate and manage with its development in 10-15 years, but also in 20-30.

“Rozwój proinnowacyjnych kompetencji w wybranych systemach edukacyjnych”.

W oparciu o wybrane przykłady dobrych praktyk oraz edukacyjnych rozwiązań takich jak w Danii, Finlandii czy Niemieczech omówiona zostaje kwestia wyboru, nauczania i upowszechniania tzw. pro-innowacyjnych kompetencji. Wniektórych krajach jak chocby Finalandia, Korea Południowa czy Izrael, dużą uwagę przywiązuje się do wyrównywania szans edukacyjnych uczniów. Wówczas, to najlepsi nauczyciele są kierowani do natrudniejszych miejsc i środowisk; niestety, pod tym względem w Polsce wciąż dzieje się na odwrót. Nie ulega wątpliwości, iż synteza dobrych praktyk winna być przeprowadzona bardzo ostrożnie I winna uwzględniać specyfikę oświatową danego kraju, z pewnością jednak w Polsce jak i w większości krajów nauka proinnowacyjnych umiejętności i kompetencji winna być nastawiona na cel długoterminowy tak, aby dzisiejsi uczniowie mogli odnależć się i zarządzać swoim rozwojem zarówno za 10-15 lat, jak i za 20-30 lat.

Słowa klucze: kompetencje pro-innowacyjne, oświata, szkoła, umiejętności, rozwiązania edukacyjne, systemy edukacyjne

„The development of pro-innovative competences in the selected education systems”.

Based on selected examples of good practices and educational solutions such as in Denmark, Finland or Germany, the issue of selection, teaching and dissemination of the so-called pro-innovative competences. In countries such as Finland, South Korea and Israel, great attention is paid to equalizing educational opportunities for students. In these countries, there are the best teachers who are just directed to the most difficult places and environments, unfortunately, in the case of Polish system of education – we have the impression – that the opposite is still happening. There is no doubt that the synthesis of good practices should be done very carefully and take into account the educational specifics of a given country, but certainly in Poland and in most countries learning pro-innovative skills and competences should be put towards the long-term goal in order to that today’s students can relate and manage with its development in 10-15 years, but also in 20-30.

Key words: pro-innovative competences, education, school, skills, educational solutions, educational systems.

Bibliography:

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 1983, ss. 357–376.

Amabile, T. M. (1997). Motivating Creativity in Organizations: On Doing What You Love and Loving what you do. California Management Review, Vol. 40 No. 1, Fall 1997.

Bastos, R.M.B. (2017). The surprising success of the Finnish educational system in a global scenario of commodified education. Revista Brasileira de Educação.vol.22 no.70 Rio de Janeiro July/Sept. 2017. Available at. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782017227040339. Last accessed 16.07.2019.

Brewer, L. (2013). Enhancing youth employability: What? Why? and How? Guide to core work skills. International Labor Organization. Available at: https://www.mygov.in/sites/default/files/user_submission/1c0e468f4fb6ab454fc579775eaf37c9.pdf; last accessed 12.08.2019.

Casner-Lotto, J., Barrington, L. (2006). Are They Really Ready to Work? Employers’ Perspectives on the Basic Knowledge and Applied Skills of New Entrants to the 21st Century US Workforce. Partnership for 21st Century Skills. Available at:https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED519465.pdf. Last accessed 5.12.2017.

Enhancing employability. (2016). Report prepared for the G20 Employment Working Group with inputs from The International Monetary Fund 2016. https://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/Enhancing-Employability-G20-Report-2016.pdf. Last accessed 08.08.2019.

Entrepreneurship Education: A Guide for Educators. (2014). European Commission, DG Enterprise and Industry. European Commission: Brussels.

European Commission, (2012). Effects and impact of entrepreneurship programmes in higher education, Brussels.

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2011). How much do educational outcomes matter in OECD countries?. Economic Policy, 26(67), 427-491.

Infosys (Firm). (2016). Amplifying human potential: education and skills for the fourth industrial revolution. Available at: http://boletines.prisadigital.com/%7B6139fde3-3fa4-42aa-83db-ca38e78b51e6%7D_Infosys-Amplifying-Human-Potential.pdf. last accessed 5.12.2017.

Jaumotte F., Pain, N. (2005). Innovation in the Business Sector. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 459, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/688727757285. Last accesed. 20.06.2019.

Kabukcu E., Creativity Process in Innovation Oriented Entrepreneurship: The case of Vakk., Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 195, 2015, ss. 1321-1329, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.307. Last accesed. 20.06.2019.

McCrory, P. (2010). Developing interest in science through emotional engagement. In:ASE Guide to Primary Science Education – New Edition, (ed.) W. Harlen, Association for Science Education, 2010.

Manyika, J., Lund, S., Auguste, B., Mendonca, L., Welsh, T., & Ramaswamy, S. (2011). An economy that works: Job creation and America’s future.Available at: http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/MGI/Research/Labor_Markets/An_economy_that_works_for_US_job_creation. last accessed 15.09.2019.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), ILO (International Labour Organisation), WB (IBRD), & IMF (International Monetary Fund). (2016). Enhancing employability. Report prepared for the G20 Employment Working Group. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/employment-and-social-policy/Enhancing-Employability-G20-Report-2016.pdf; last accessed 5.12.2017.

Oslo Manual. (1997), Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological, OECD, Paris.

Szkoła dla innowatora. (2018). Kształtowanie kompetencji proinnowacyjnych. Kalisz: Ośrodek Doskonalenia Nauczycieli.

Strategy for the years 2014–2025. LUMA Centre Finland. https://www.luma.fi/en/files/2017/03/lcf-strategy-2014-2025.pdf. Last accessed 10.09.2019.

World Economic Forum. (2016). The future of jobs: Employment, skills and workforce strategy for the fourth industrial revolution.World Economic Forum, Geneva.