About two years ago the European public health turmoil due to the COVID-19 pandemic began. All countries were affected, but the virus didn’t have the same impact on all of them. Specifically during the first wave, up to May 2020, some countries were hit hard, while some others seemed to go through it with less damage. In his paper, The underlying factors of the COVID-19 spatially uneven spread. Initial evidence from regions in nine EU countries, published at the Regional Science Policy and Practice Journal, Dr Nikos Kapitsinis takes a look at the factors for this uneven spread but from a regional viewpoint.

Nine countries (Germany, France, Greece, Portugal, Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden, Spain) were placed under the microscope for their mortality rate due to COVID-19. Lombardy in Italy and Communidad de Madrid in Spain were the two regions with the highest mortality rate, reaching 136 and 122 deaths per 100.000 inhabitants respectively. On the other hand, five regions didn’t record any deaths at all, with four of them situated in Greece (Ipeiros, Thessalia, Sterea Ellada, Notio Aigaio) and one in Portugal (Região Autónoma da Madeira). So, how did this happen?

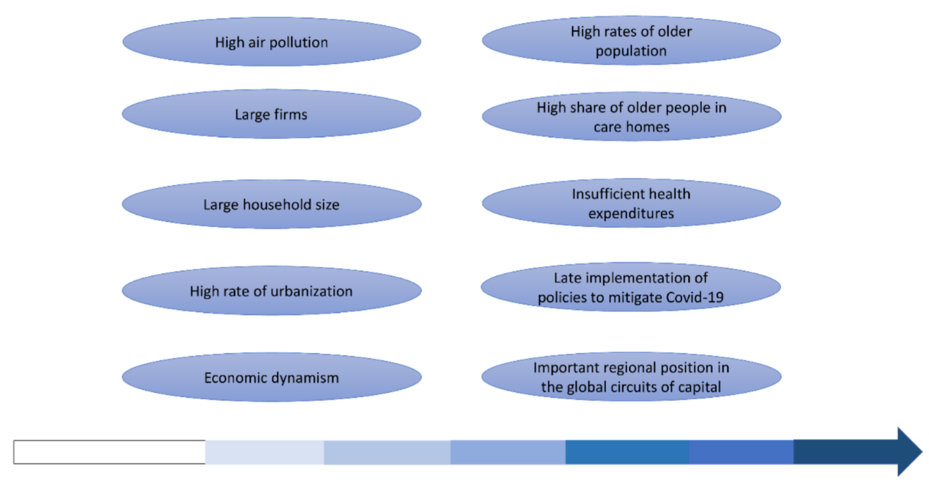

“A region with high mortality is likely to have large households and firms, and those with a big share of people over 65 years old recorded the highest mortality. Mortality is greater where a high rate of elderly people living in care homes is identified”, Dr Kapitsinis notes.

Dense population, people of elderly age, who are more susceptible to contract and get sick from a disease, high levels of pollution and regional inter-connectivity are addressed as factors for this regional disparity in deaths.

As with his study at national level, Dr Kapitsinis notes that a solid healthcare system, on the other hand, is considered to be a mitigating factor for lower mortality rates. “Regions with a higher number of doctors and hospital beds per 100,000 inhabitants recorded lower mortality rates. Those with a below-average number of hospital beds showed much higher mortality than those where the number was above average (28 victims to 11)”.

Late implementation of effective measures for preventing the spread of the virus and the lack of the EU-wide coordination are also key elements for this disparity in deaths across EU. “The first case in Europe was recorded two months after the first outbreak in China, giving European countries time to act. Delays in addressing and negligence in containing outbreaks through ‘test, trace, and isolate’ played a part in their failure to control the pandemic”.

Countries that reacted more quickly to the pandemic after recording their first death due to the virus, like Portugal, Austria and Greece, were less affected in the long-run.

Yet, there are still positive outcomes to be noted from the years-long pandemic. Dr Kapitsinis states that “despite its terrible toll, COVID-19 could revolutionise the policy discourse around health systems, as well as working and living patterns”, and he adds“Containment policies, which seek to test, track and isolate cases, proved to be the most efficient way to reduce mortality rates.” And to do so, “All these will require more financial investment in health systems”.

Author:

Nikos Kapitsinis, YOUTHShare & Visiting Researcher, Department of Geography, University of the Aegean

Adaptation:

Zoopigi Touvra, PhD Candidate, University of the Aegean