One of the indirect consequences of financial crises is that in some sense all the focus gets shifted to financial issues. Of course, this is a reasonable reaction. But, just like the occurrence of a crisis allows us to reflect on the viability and usefulness of past actions, we should also consider whether the shift of focus to practical urgencies has a disorientating effect even after the initial turmoil is over.

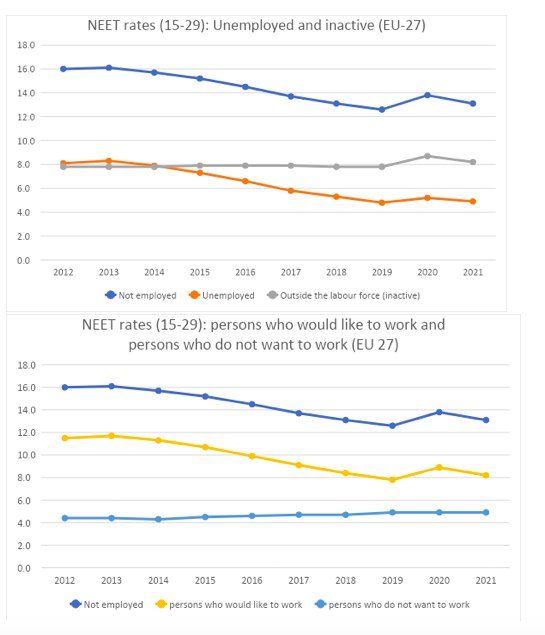

Starting in 2013 there was a drop in the youth unemployment and NEET rates (although not necessarily in every Member State). One thing worth considering when analysing the events, is at what level the improvement was in fact a result of the policies implemented by Member States to support NEETs or whether it could be attributed to the economic recovery in general.

Nevertheless there is another issue that draws attention. Taking a closer look at the subgroups of the unemployed and the inactive, one observes that the decrease in the overall NEET rate is solely due to the decrease in the unemployed. Inasmuch as the goal of policies like the Youth Guarantee was not only to reduce youth unemployment but also inactivity, it would appear that regarding the latter part they cannot be deemed effective.

During the last decade the percentage of young people who do not want to work ranges between 4 and 5 percent, while that of the inactive is stable at about 8 percent, as indicated in the graphs below. A first question is whether all the people who answer that they do not want to work do not actually need a job or if some of them are in a state of disengagement. A second question that arises, concerns those who compose the difference between the two groups: there is a 3.5% to 4% of the 15-29 population who would like to work but they are not registered as unemployed.

One valid explanation lies in the inability of Public Employment Services and relevant services to reach these groups. Several scholars have investigated this situation and provided insight on its sources (for a brief review see also the other article from our project in this YEM issue). The reinforced Youth Guarantee intends to achieve some progress in this regard. However, in some cases communication fails not only because of the shortcomings of the transmitter or the channel; it may also be that the receiver is not well tuned.

Before the 2007-2008 financial crisis, European youth policies were concerned with employment and mobility, but also with promoting active citizenship. In the subsequent European Youth Strategies it is acknowledged that socially oriented and participation behaviours such as volunteering are increasingly taking the form of individualised actions such as consumer support and media attention (European Commission, 2018). The participation of more young people in the public debate is an important contributing factor to better informed and more effective youth policies. Furthermore, such public participation leads to networking; and larger networks of active youths increase the chances of reaching people of vulnerable groups, contributing in this way to the desirable labour market activation and avoiding social exclusion.

Active citizenship presupposes trust in social structures and at the same time it can further enhance it. During the years of recession, the levels of trust in institutions declined significantly; in the first couple of months from the Covid-19 outbreak, the Eurobarometer (European Commission 2021) reported a boost in trust in the EU (still, not exceptionally high – at 49%), but this was not the case for national governments (36%) and parliaments (35%).

Low levels of citizens’ trust in institutions mean that people do not count on public institutions to solve their problems; they may be hesitant to register to the unemployment records, and they may even not bother to get informed about public calls to join employment programmes. These are symptoms of discouragement and disengagement, bearing all the potential risks for the individual and the society (mental health issues, anti-social behaviour, vulnerability to populism etc); but under this scope, their source is not simply the skills mismatches.

On the one hand, governmental institutions have to build trust by taking action for the creation of more jobs and ensuring the term “good quality offer” of the YGs (Escudero & Murelo, 2017).

At the same time, the focus on fostering social cohesion should be renewed. Promoting active citizenship can be a key factor; but even simpler practices such as the promotion of participation in extracurricular activities have been proven to have a positive impact (You, 2020) Such policies can be effectively implemented through secondary education; but this would require a partial shift from the current trend of developing education in complete alignment with the labour market trends.

From our side, in the Cowork4YOUTH project, we are starting to explore how coworking spaces can act as places of networking which -among the other, operational, economic and productivity benefits- can have a broader role in the society by fostering social engagement and contributing to social cohesion.

References

European Commission (2021) Eurobarometer: Trust in the European Union has increased since last summer [press release]. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_1867

European Commission Communication COM(2018) 269. Engaging, Connecting and Empowering young people: a new EU Youth Strategy, Brussels, 22.5.2018.

Escudero, V. and Mourelo, E.L. (2017) The European Youth Guarantee: A systematic review of its implementation across countries. Research Department Working Paper No. 21. August 2017. International Labour Office.

You JW. The Relationship Between Participation in Extracurricular Activities, Interaction, Satisfaction With Academic Major, and Career Motivation. Journal of Career Development. 2020;47(4):454-468.