This ain’t livin’, this ain’t livin’

No, no baby, this ain’t livin’

No, no, no, no

Inflation no chance

To increase finance

Bills pile up sky high

Send that boy off to die

Hang-ups, let downs

Bad breaks, set backs

Natural fact is

Oh honey that I can’t pay my taxes

In the soul classic from 1971, with the even more mesmerising music video from 1994 Harlem, Marvin Gaye recites his “Inner City Blues”; the blues of the repressed minorities of the American cities. It is a compelling depiction of the escalating disappointment, poverty, unemployment, hopelessness, racial discrimination, political representation crisis and the search for identity prevalent during the 1970s. After the dreamy 1960s, comes a decade of disillusionment, economic crisis, institutionalised racialism and unequal share of the financial burden upon the youth and the minorities.

In his beautiful musical drawing of the inner city, Marvin Gaye deals critically with the present of the early 1970s, rather than the continuity or break with the past. Yet, urban sociology had already been investigating the aforementioned phenomena in combination with deviancy mapping. Since the beginnings of the 20th century the Chicago School of sociology, also known as Ecological School, applied a series of, innovative for the period, mixed methods in order to explain the relationship between social phenomena and the space. Ethnographic observation, census and policing statistics, GDP and self-reporting life histories were employed to provide a balanced, yet rough, explanation of the reciprocal relationship between space and social evolution. The Chicago School’s approach, no matter how over-reliant on empirical data and idealism, produced one of the most compelling explanations of urban evolution.

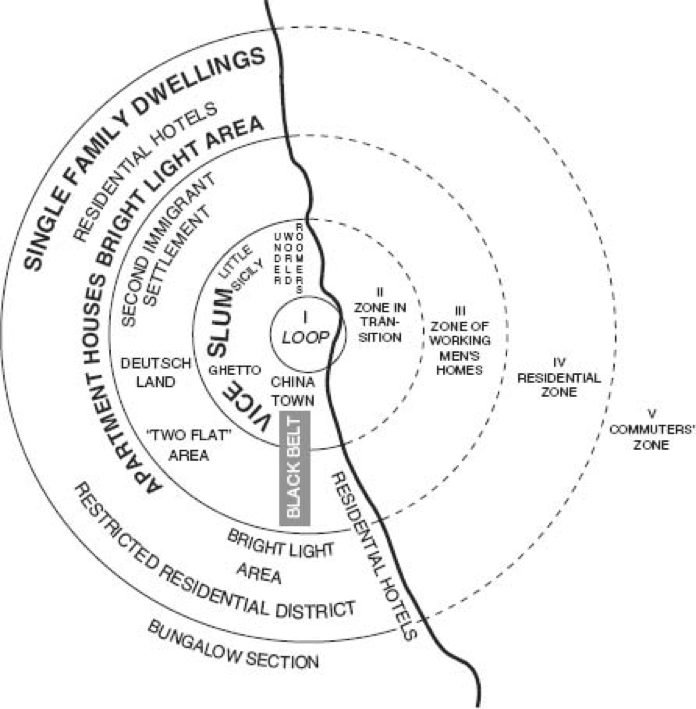

Under the general umbrella of the newly introduced statistical maps, the Ecological School studied Chicago and produced ‘spot maps’ demonstrating the location of social problems, ‘rate maps’ dividing the city into blocks to demonstrate census data – the predecessor of location quotient – and ‘zone maps’ presenting the clustering of problems in the city. By the use of the latter, Ernest Burgess theorised the radial expansion of the cites into concentric rings described as zones. The city centre is the business area and around it lies the transition zone or slum area. The next zone houses the workers followed by the residential area, the suburbs and the commuters’ zone. Consequently, the social class divisions would generally follow those zones and the social mobility of groups was not only conceptual but most of the times spatial too. In other words, the increase of incomes or the entrance of a lower class (e.g. a migration wave) would “move” families centrifugally towards the outer zones; whereas, the decreased incomes would “push” families towards the slum area.

Despite the fact that this image is subconsciously confirmed in our European perception of the American cities, this type of social dynamic can hardly be confirmed at least after the 1950s. As a matter of fact, our perception is owed to the American film industry. Even for Chicago, its proximity to Lake Superior altered the expansion of the city and the Ecological School sociologists were aware of that.

Nonetheless, there is yet another reason that deconstructs the social zones’ perception of the cities. To a large degree, the zone mapping corresponds to a certain organisation of the production process; with businesses and businessmen/women, their personnel, the self-employed and the temporarily or long-term unemployed manpower and the economically inactive. Since the late 1970, however, the gradual deconstruction of the production process in the Western world, with the prominence of knowledge and information in the production process at the expense of traditional means of production and their related skills, alter also the social relations inherent in the production process. Labour flexibilisation, teleworking, the reservation of high-end skills for only a few job posts at the apex of the hierarchy, the replacement of manual work by computer-based, but still menial work, gradually leads to the disengagement between space and social evolution.

Either because of the platform economy or not, essential services tend to be contracted-out to freelancers. Piecemeal work, particularly connected to teleworking, is becoming more and more common. A new precariat arises consisting of, primarily, young, usually educated workers, who spend considerable time in unemployment too. Becoming a NEET is not a distant but rather a foreseeable possibility.

The person Not in Employment Education or Training is not contained in the slum zone next to the city centre anymore. The NEETs are spread geographically exactly because the space receives a new meaning for the precarious job relations. Space now becomes permeable. The urban zones do not delineate types of jobs and furthermore class divisions. The precarious worker, who is most likely the former and the future NEET, offers his/her services wherever needed.

Since 1971 and since the Chicago School of sociology the world has changed drastically. Marvin Gaye’s (inner) city blues, however, remain shockingly relevant:

Rockets, moon shots

Spend it on the have nots

Money, we make it

Fore we see it you take it