Note

This is a summary of a prefinal article to be submitted in a scientific journal especially adapted for the Youth Employment Magazine. Adaptation: Zoe Touvra, PhD candidate University of the Aegean

The recent global economic recession accounts for the significant rise of the Not in Employment, Education or Training population (NEETs) in Southern European countries with semi-peripheral characteristics and less-advanced capitalism (Thurlby-Campbell and Bell, 2017). At the same time Active Labour Market Policies, and most notably the Youth Guarantee action plan (YG) have been employed to facilitate the constant contact of young people with the labour market. The EU member states committed to its implementation through the European Council Recommendation of April 2013. Almost a decade later, the effectiveness question is pressing one, especially from a regional perspective.

The already expressed criticism against the YG policy framework, usually revolves around the supply side perspective applied to the unemployment phenomenon which centralised the concept of employability or “the character or quality of being employable” (McQuaid and Lindsay, 2005:3). The supply side perspective of this argument connected labour to the improvement of an individual’s personal work skills in order to improve their “accessibility to the market” (Hillage and Pollard, 1998). The “question of the individual” inescapably prevailed transferring the burden of transformation to the unemployed individual. In a milder, yet faithful to this perspective, approach, the YG seeks actively to up-skill, or re-skill the unemployed individual in order to improve its access to the labour market. Schemes of (self-) entrepreneurship, training courses, on-the-job training or waged labour subsidies have not been positively proven to be catalysts for quality employment (Pasqual and Martin, 2017). Although, YG eventually reduces unemployment, the connection of the unemployed youth to quality jobs remains a working hypothesis.

Besides the aforementioned general criticism, the present study re-approaches statistical data to point towards a different line of criticism against the effectiveness of YG; one that centralises spatial heterogeneity.

The high contribution of Spain and Italy to the total YG programme enrolment puts them in the spotlight, as these countries, together with France, account for 47% of the total YG programme enrolment (European Commission, 2018). At the same time, Spain and Italy show a high spatial heterogeneity between their southern and northern regions in terms of poverty and income inequality (Benedetti et al., 2020). Indeed, the most illustrative, intra-national examples of spatial heterogeneity in southern Europe are Spain, Italy and Greece, with the former two countries being divided between their southern and northern regions in terms of poverty and income inequality (Benedetti et al., 2020) and the latter one having practically only two regions out of thirteen with a GDP per capita above the 75% EU threshold. A focus on Italy and Spain would reveal that ultimately addressing the NEET phenomenon is of topical interest.

In Italy YG is managed by the National Agency for Active Labour Policies (ANPAL) under the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies. ANPAL allocates funds among the regions, while each region develops its own regional implementation policies through regional employment centres (It2). To that extent the regional authorities enjoy certain degree of autonomy in developing tailored policies.

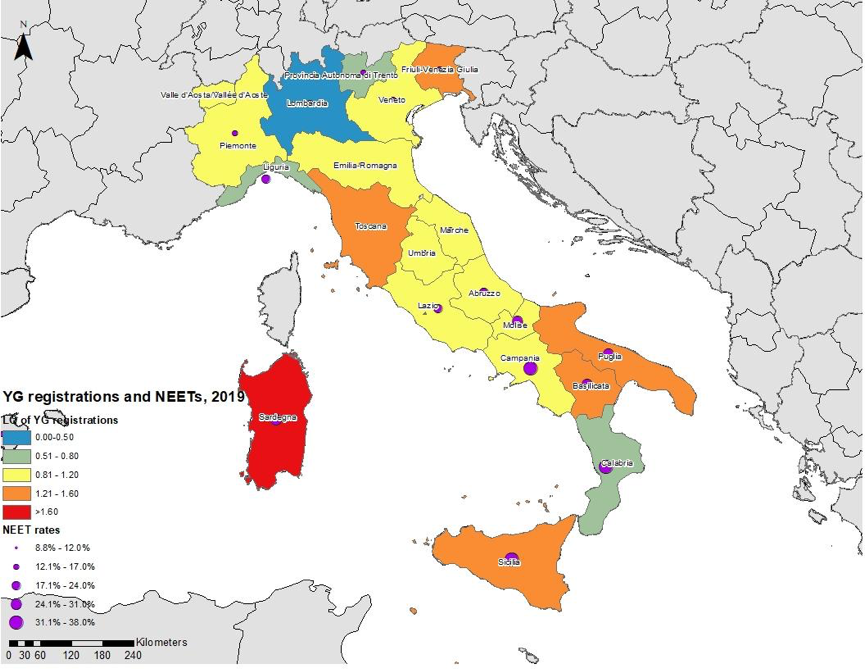

Figure 1 shows that southern regions that record high NEET rates tend to have more YG enrolees. However, certain southern regions (e.g. Calabria or Campania) do not follow the same trend. In contrast, Tuscany, and Friuli-Venezia Giulia -both economically prosperous regions- have significantly lower NEET rates while experiencing high concentration of YG enrolments. A simplified interpretation would ascertain that more prosperous regions have a more efficient application of the YG program. Nonetheless, the quantitative analysis leads to a paradox: the most recent data indicate that in most of those prosperous regions, the YG enrolments are higher than the NEET numbers in the region. Key informants attribute that to southern regional authorities pushing young people to enrol in more prosperous regions. Under these circumstances, YG enrolments should be conceived as potential internal interregional migrants, especially in short distances. Of course, this is not an economy underpinned migration but rather an institutional, administrative reorganization between short-distanced regions. Overall, in addition to structural, economic parameters, geographic and institutional parameters play an important role in the spatial distribution of YG enrolees. The top-down design of the YG programme establishes a situation of continuous precariousness for the YG enrolees rather than an induction to quality labour positions.

Figure 1. Location Quotient (LQ(a)) revealing regional over/under concentration of YG registrations compared to the national level, and regional NEET rates, Italy, 2019.

Figure 1. Location Quotient (LQ(a)) revealing regional over/under concentration of YG registrations compared to the national level, and regional NEET rates, Italy, 2019.

Source: ANPAL, SEPE reports and EU labour force survey, compiled by the authors.

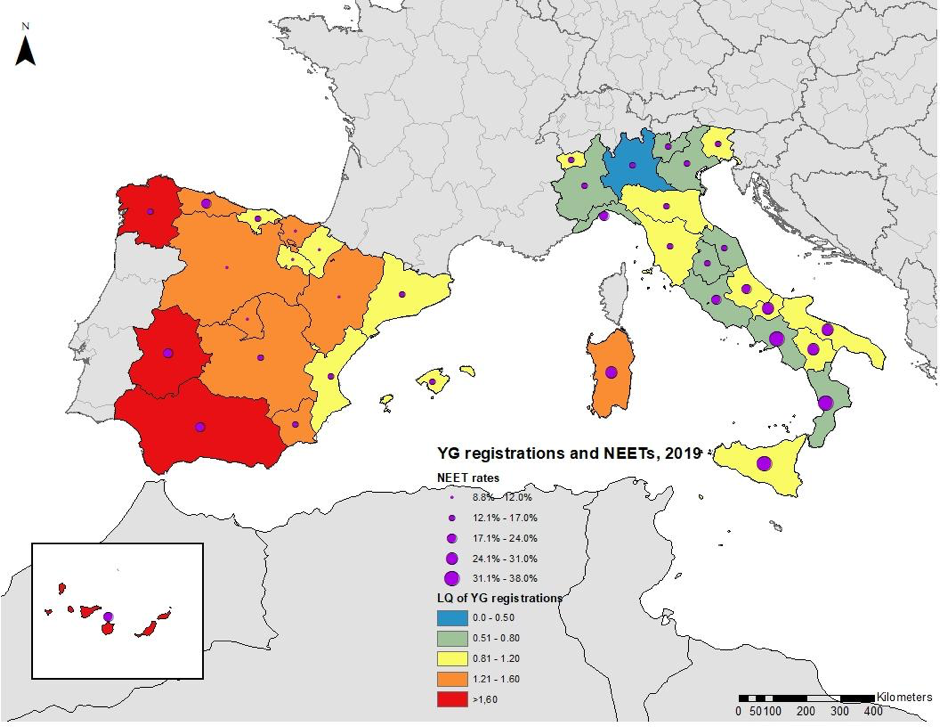

The Spanish YG is managed by the State Public Employment Service (SEPE) under the Ministry of Labour and Social economy. SEPE sets the funding allocation and provide the regulatory conditions, leaving implementation and execution to the involved regions with a high degree of autonomy. Figure 2 shows that southern regions that record high NEET rates tend to have more YG enrolees. In the same path, the lowest concentration of enrolees and NEET rates are observed in Catalonia and in the Valencian Community –both prosperous regions. Nonetheless, the key informants interviewed were highly critical to the YG. Institutional-operational deficiencies in the Spanish YG framework are triggered by the lack of coordination According to a key stakeholder the fragmentation that penetrates the institutional structure causes a low connectivity between enterprises and National and regional authorities as a result high records of YG enrolment coincides with a broad sense of underperformance by the interviewees of the study. The Spanish YG register does not delete young people once they have access to an offer of employment, education or training, unless the young person actively requests to be deleted. Thus, the information provided is cumulative. Thus, the Spanish registry does not provide information on the details of registrants, but on registrations. The high concentration of YG registrations in Spain is not so much the result of a successful application but is related to the insufficient and regionally uncoordinated registration procedures.

Figure 2: Location Quotient (LQ(b)) revealing regional over/under concentration of YG registrants, calculated for the aggregate of NUTS-2 regions of Spain and Italy, 2019.

Figure 2: Location Quotient (LQ(b)) revealing regional over/under concentration of YG registrants, calculated for the aggregate of NUTS-2 regions of Spain and Italy, 2019.

Source: ANPAL, SEPE reports and EU labour force survey, compiled by the authors.

Prima facie it is the institutional structure of the YG that gives a distorted picture of the distribution of YG enrolments between regions. In Italy, young people participating in the YG are encouraged to register in the most prosperous regions in the hope of finding a job, retaining by that the status of potential interregional migrants, thus serving a latent youth labour mobility. Similarly, in Spain, keeping young people registered even after receiving a job offer causes a two-way continuity from the employment situation to that of unemployment (NEETs) and creates a different kind of latent mobility. These two types of latent mobility may be seen as the result of the misapplication of the YG. Nevertheless, amid a recessionary and crisis-prone environment they only replicate the supply-side employability. Small firms in the Italian South concentrated in sectors with low technological and innovative capacity require relatively low skills from the workforce. While, in Spain the continuous redistribution of a limited welfare budget among the same number of beneficiaries perpetuates the ‘flexibilization’ of precarious young workers.

Bibliography

Thurlby-Campbell, I., Bell, L., 2015. Agency, Structure and the NEET Policy Problem

The Experiences of Young People. Bloomsbury Academic.

McQuaid, R.W. and Lindsay, C., 2005. The concept of employability. Urban studies, 42(2), pp.197-219.

Hillage, J. and Pollard, E. (1998) Employability: Developing a Framework for Policy Analysis. London: DfEE.

Serrano Pascual, A. and Martín Martín, P., 2017. From ‘Employability’ to ‘Entrepreneuriality’ in Spain: youth in the spotlight in times of crisis. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(7), pp.798-821.

Benedetti, I., Crescenzi, F. and Laureti, T., 2020. Measuring Uncertainty for Poverty Indicators at Regional Level: The Case of Mediterranean Countries. Sustainability, 12(19), p.8159.

European Commission (EC), 2018. Data collection for monitoring of Youth Guarantee schemes 2017, December 2018. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19159&langId=ga

Authors

Effie Emmanouil, PhD candidate University of the Aegean

George Chatzichristos, PhD University of the Aegean

Andrew Herod, Professor University of Georgia

Stelios Gialis, Associate Professor University of the Aegean