Even with the deaths that COVID-19 caused once it arrived in Europe, the numbers don’t add up. Dr Nikos Kapitsinis, visiting researcher at the Department of Geography of the University of the Aegean and member of the Labour Geography Research Lab, in two papers published in The Conversation and the LSE Blog introduces the term “excess mortality” to describe this abnormality. ”When looking across a sample of 79 high-, middle- and low-income countries, overall there were 3.7 million more deaths in 2020 compared with the average for 2015-19 – an excess of 13%. This figure reflects not only official COVID deaths, but those caused by the virus yet not recorded as such”, he notes.

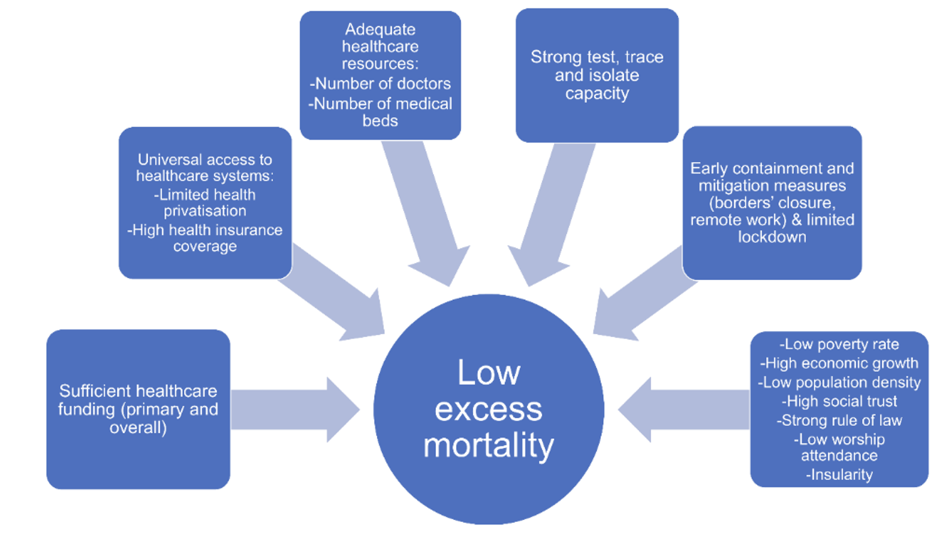

Nonetheless, even if official CoVID-19 deaths were taken into consideration, their geography is notably uneven. But why are there such sharp differences in the numbers? Dr Kapitsinis lists the main factors deemed to have played a significant role:

Healthcare capacity and universal access to healthcare.

“To handle the COVID health emergency well, countries needed to be prepared. Those entering the pandemic with insufficiently funded healthcare systems and limited resources were more likely to be overwhelmed and have high levels of excess death”, he notes. Effective primary healthcare is of high importance. Being able to monitor patients with mild symptoms from their home reduces the risk of being hospitalised and spread the virus further. But effective healthcare doesn’t stand alone. Universal healthcare is an interconnected key factor.“The poverty rate proved to be a powerful driver of excess mortality. It often restricts access to healthcare, leads to poor living conditions and limits the capacity to physically distance.”

Governmental response

Having a strong test, trace and isolate (TTI) system was strongly associated with fewer deaths.”, Dr Kapitsinis notes. “[…] countries with the longest and most stringent lockdowns were likely to have higher rather than lower excess mortality. Governments that used them did so because they failed to act in time.” This shows that strict measures do not grant success of their implementation.

Location

“Geographically isolated island countries, such as New Zealand and Iceland, were more likely to record low excess mortality. They were better placed to control their borders and detect people infected with COVID on arrival”. As shown in the framework of the YOUTHShare project and its spin off e-ResLab Aegean dashboard, gGeography constitutes a key element in halting the virus spread.

Rule of law

Quite interestingly, the final factor raises a significant discussion. Dr Kapitsinis identified that “Countries with a high value on the rule of law index did better, since the effective implementation of emergency policies could facilitate a country’s response to the pandemic. Societies with fragile social trust were likely to demonstrate high excess mortality, since it weakens collectivism and social solidarity”.

The COVID-19 pandemic, during the last two years, has granted us valuable experience, not only to address the next pandemic but also to value the importance of social cohesion. One can stress the importance of sufficient funding for boosting the preparedness of the healthcare system prior to any new pandemic outbursts in order to make sure that response is timely and adequate. But at the end of the day, even the increased funding for healthcare cannot be reduced to a mere cost/benefit analysis. It’s a direct policy result of social solidarity.

Author:

Nikos Kapitsinis, YOUTHShare & Visiting Researcher, Department of Geography, University of the Aegean

Adaptation:

Zoopigi Touvra, PhD Candidate, University of the Aegean