For the 77th time, Europe commemorated the end of the Second World War. A period that among tremendous disasters, lofty values and base instincts, also left some important lessons to humanity.

A lesser known by-product of the WWII period is the emergence of the scientific field of Operations Research. What today is an analytical method of problem solving and decision making in the management of organisations, was at the time an absolute necessity in order to maximise the impact of wartime operations through statistics and mathematical equations. Observations such as the rate of survival of friendly forces, the rate of successfully delivered cargo shipments, or the rate of damage against the enemy were decisive indicators for the outcome of the war.

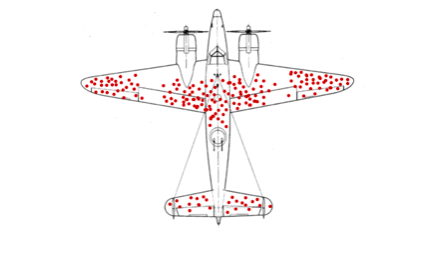

We owe to Operations Research and to the graph presented here one of the most important lessons in research and organisation management. The Statistical Research Group (SRG), a classified US program, received a request from the american navy to determine the optimal amount of armour that bombers should carry in order to balance between efficiency and safety. The “mapping” of the bullets received by returning bombers should be the perfect answer to the question of where the armour had to be placed: more bullet holes should indicate the areas requiring heavier armouring. Or not?

Statistician Abraham Wald observed that the bullet mapping was based on the bombers that managed to return from their missions; yet, the bombers that could really reveal the weak spots that required extra armour plates, were the ones that got shot down and failed to return. By identifying the logical error, Wald saved the game and identified what is today known as survival bias.

Besides its wartime use, survival bias is actually endemic in every human activity entailing performance measurement. In that context, social intervention projects, given the human factor involved, present a significantly more complex framework of performance measurement against set targets, where the trap of survival bias lurks. In different contexts, survival bias is considered a specific category of sampling bias, which refers to conditions where certain members of the researched population are more likely to be part of a sample than others.

The YOUTHShare project set out in 2018 to deploy a multiscalar strategy combining research and social intervention with a view to designing and piloting different methods of addressing youth unemployment in South Europe. In that framework, based on their concentration and the existing bibliography, it defined the most vulnerable among the local NEET population, namely migrants, asylum seekers and women. Nevertheless, it soon became apparent to the researchers and to the Key Account Managers of the Transnational Employment Centre alike, that a socially imposed status is different from the objective reality of vulnerability. Being a migrant or a woman does not equate to vulnerability. A close engagement of the field provided even deeper reflections. Vulnerability does not equate to a skills gap either – at least not in the dominant sense of skills as provided through formal education. For South European societies the crux of vulnerability was to be found in disengagement from the labour market. The Key Account Managers have recorded cases of socially skilful asylum seekers that managed to remain engaged to the labour market despite brief periods of unemployment or highly educated women that were disappointed by their contact with the labour market.

Since this insight was gained as the YOUTHShare project was already under way, the predetermined target groups were found to only partially reflect the essence of the NEET phenomenon in the coastal and insular regions of Greece, Cyprus, Italy and Spain. Given that the Transnational Employment Centre could not and should not refuse support to NEETs that do not fall within the refined vulnerability perspective, the Key Account Managers were exposed to survival bias in the interpretation of the, otherwise impressive, results of the project.

Until today, more than 700 NEETs have received psycho-social counseling, CV editing, soft skills training and job matching by the local branches of the YOUTHShare Transnational Employment Centre. 678 former NEETs have registered at the e-learning platform and enhanced their skills in resilient sectors of the Mediterranean economy. But how many among them were essentially vulnerable? How many among them were “re-engaged” with the labour market, while they have never been disengaged? We have grounds to believe that a percentage of them, falling neatly in the target group requirements of the project, reached out to the Transnational Employment Centre rather than be reached out.

The YOUTHShare project and its staff, researchers and practitioners, soon became conscious of their exposure to this survival bias. The first question arising is the gravity of this “failure”; in other words, are we helping with the problem if we are not helping only the most vulnerable? The answer is pretty much obvious. Regardless of their level of vulnerability, many former NEETs have actually received support, training and hands-on experience and the YOUTHShare project has had a genuinely positive effect.

Under that light, the question changes direction. The target-based performance measurement in funded programs like this leaves limited room for adjustments. Could the impact have been deeper with a more flexible design? Possibly, an impact-driven redesign of the targets and the intervention after the completion of milestones could maximise the impact and provide the “sweet spot” between mistakes and biases.